The physical properties of particulate materials can influence a wide range of material behaviors including, for example, reaction and dissolution rates, how easily ingredients flow and mix, or compressibility and abrasivity. From a manufacturing and development perspective, some of the most important physical properties to measure are:

Depending upon the material of interest, some or all of these could be important and they may even be interrelated: e.g. surface area and particle size.

The aim of this particle characterization guide is to provide a basic grounding in the main particle characterization techniques currently in use within industry and academia. It assumes no prior knowledge of particle characterization theory or instrumentation and is ideal for those new to particle characterization, or those wishing to reinforce their knowledge in the field. The guide covers introductory basics, particle sizing theory and particle characterization instrumentation, as well as a quick reference guide to help you decide which techniques might be most appropriate for your particle characterization needs.

For the full guide to particle characterization, please sign up below for free to access the full copy and PDF download.

The aim of this guide is to provide a basic grounding in the main particle characterization techniques currently in use within industry and academia. It assumes no prior knowledge of particle characterization theory or instrumentation and is ideal for those new to particle characterization, or those wishing to reinforce their knowledge in the field. The guide covers introductory basics, particle sizing theory and particle characterization instrumentation, as well as a quick reference guide to help you decide which techniques might be most appropriate for your particle characterization needs. It is not inclusive of all particle characterization techniques; more information can be found at www.malvernpanalytical.com.

At the most basic level, we can define a particle as being a discrete sub-portion of a substance. For the purposes of this guide, we shall narrow the definition to include solid particles, liquid droplets or gas bubbles with physical dimensions ranging from sub-nanometer to several millimeters in size.

There are two main reasons why many industries routinely employ particle characterization techniques:

In an increasingly competitive global economy, better control of product quality delivers real economic benefits such as:

In addition to controlling product quality, a better understanding of how particle properties affect your products, ingredients and processes will allow you to:

In addition to chemical composition, the behavior of particulate materials is often dominated by the physical properties of the constituent particles. These can influence a wide range of material properties including, for example, reaction and dissolution rates, how easily ingredients flow and mix, or compressibility and abrasivity. From a manufacturing and development perspective, some of the most important physical properties to measure are:

Depending upon the material of interest, some or all of these could be important and they may even be interrelated: e.g. surface area and particle size. For the purposes of this guide, we will concentrate on two of the most significant and easily measured properties: particle size and particle shape.

By far the most important physical property of particulate samples is particle size. Particle size measurement is routinely carried out across a wide range of industries and is often a critical parameter in the manufacture of many products. Particle size has a direct influence on material properties such as:

Measuring particle size and understanding how it affects your products and processes can be critical to the success of many manufacturing businesses.

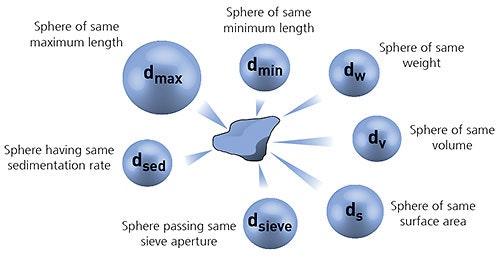

Particles are 3-dimensional objects, and unless they are perfect spheres (e.g. emulsions or bubbles), they cannot be fully described by a single dimension such as a radius or diameter.

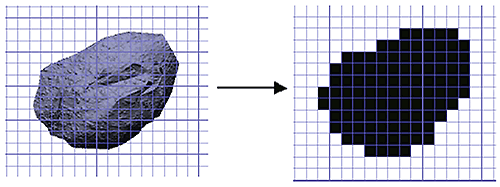

In order to simplify the measurement process, it is often convenient to define the particle size using the concept of equivalent spheres. In this case the particle size is defined by the diameter of an equivalent sphere having the same property (such as volume or mass) as the actual particle. It is important to realize that different measurement techniques use different equivalent sphere models and therefore will not necessarily each give exactly the same result for the particle diameter.

Figure 1: Illustration of the concept of equivalent spheres

The equivalent sphere concept works very well for regular shaped particles. However, it may not always be appropriate for irregularly-shaped particles, such as needles or plates, where the size in at least one dimension can differ significantly from that of the other dimensions.

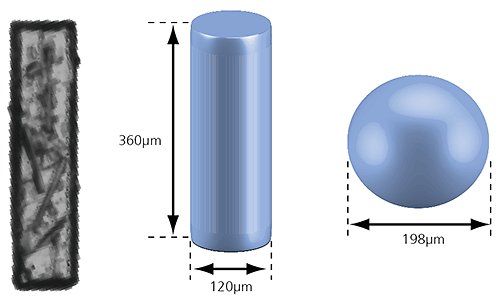

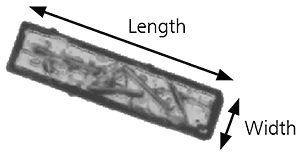

Figure 2: Illustration of the volume equivalent rod and sphere of a needle-shaped particle

In the case of the rod-shaped particle shown in the image above, a volume equivalent sphere would give a particle diameter of 198µm, which is not a very accurate description of its true dimensions. However, we can also define the particle as a cylinder with the same volume which has a length of 360µm and a width of 120µm. This approach more accurately describes the size of the particle and may provide a better understanding of the behavior of this particle during processing or handling, for example.

Many particle sizing techniques are based on a simple 1-dimensional sphere equivalent measuring concept, and this is often perfectly adequate for the required application. Measuring particle size in two or more dimensions can sometimes be desirable but can also present some significant measurement and data analysis challenges. Therefore careful consideration is advisable when choosing the most appropriate particle sizing technique for your application.

Unless the sample you wish to characterize is perfectly monodisperse, i.e. every single particle it contains has exactly the same dimensions, it will consist of a statistical distribution of particles of different sizes. It is common practice to represent this distribution either in the form of a frequency distribution curve, or a cumulative (undersize) distribution curve.

A particle size distribution can be represented in different ways with respect to the weighting of individual particles. The weighting mechanism will depend upon the measuring principle being used.

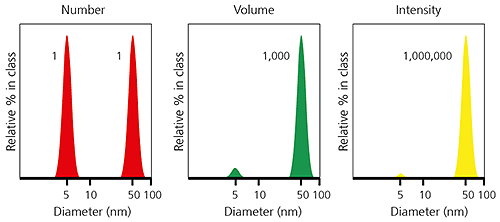

A counting technique such as image analysis will give a number-weighted distribution, in which each particle is given equal weighting irrespective of its size. This is most often useful when knowing the absolute number of particles is important - in foreign particle detection for example - or where high resolution (particle by particle) is required.

Static light scattering techniques such as laser diffraction will give a volume-weighted distribution. Here the contribution of each particle in the distribution relates to the volume of that particle (equivalent to mass if the density is uniform), i.e. the relative contribution will be proportional to (size)3. This is often extremely useful from a commercial perspective as the distribution represents the composition of the sample in terms of its volume/mass, and therefore its potential worth.

Dynamic light scattering techniques will give an intensity-weighted distribution, where the contribution of each particle in the distribution relates to the intensity of light scattered by the particle. For example, using the Rayleigh approximation, the relative contribution for very small particles will be proportional to (size) 6 .

When comparing particle size data for the same sample measured by different techniques, it is important to realize that the types of distribution being measured and reported can produce very different particle size results. This is clearly illustrated in the example below, for a sample consisting of equal numbers of particles with diameters of 5 nm and 50 nm. The number-weighted distribution gives equal weighting to both types of particles, emphasising the presence of the finer 5 nm particles, whereas the intensity-weighted distribution has a signal one million times higher for the coarser 50 nm particles. The volume-weighted distribution is intermediate between the two.

Figure 3: Example of number-, volume- and intensity-weighted particle size distributions for the same sample.

It is possible to convert particle size data from one type of distribution to another; however, this requires certain assumptions about the form of the particle and its physical properties. One should not necessarily expect, for example, a volume-weighted particle size distribution measured using image analysis to agree exactly with a particle size distribution measured by laser diffraction.

"There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics."

Twain/Disraeli

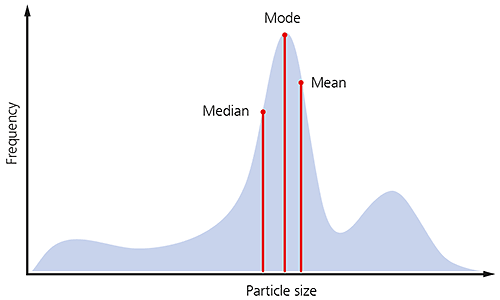

In order to simplify the interpretation of particle size distribution data, a range of statistical parameters can be calculated and reported. The choice of the most appropriate statistical parameter for any given sample will depend upon how that data will be used and with what it will be compared. For example, if you wanted to report the most common particle size in your sample you could choose between the following parameters:

• mean - 'average' size of a population

• median - size in the middle of a frequency distribution

• mode - size with highest frequency

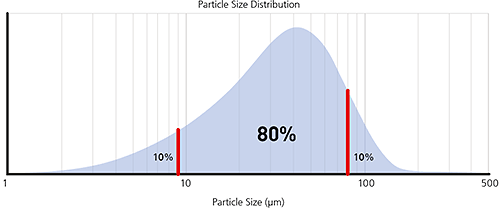

If the shape of the particle size distribution is asymmetric, as is often the case for many samples, you would not expect these three parameters to be exactly equivalent, as illustrated below.

Figure 4: Illustration of the median mode and mean for a particle size distribution.

There are many different means that can be defined, depending upon how the distribution data are collected and analyzed. The three most commonly used for particle sizing are described below.

1. Number length mean D[1,0] or Xnl

The number length mean, often referred to as the arithmetic mean, is most important when the number of particles is of interest, e.g. in particle counting applications. It can only be calculated if we know the total number of particles in the sample, and is therefore limited to particle counting applications.

2. Surface area moment mean D[3, 2] or Xsv

The surface area mean (Sauter Mean Diameter) is most relevant when the specific surface area is important e.g. bioavailability, reactivity, dissolution. It is most sensitive to the presence of fine particulates in the size distribution.

3. Volume moment mean D[4, 3] or Xvm

The volume moment mean (De Brouckere Mean Diameter) is relevant for many samples as it reflects the size of those particles which constitute the bulk of the sample volume. It is most sensitive to the presence of large particulates in the size distribution.

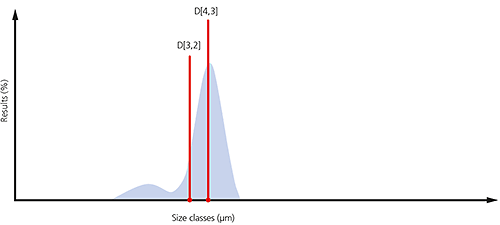

An example of the surface area and volume moment means is shown in the particle size distribution below. If the aim is to monitor the size of the coarse particulates that make up the bulk of this sample, then the D[4,3] would be most appropriate. If, on the other hand, it is actually more important to monitor the proportion of fines present, then it might be more appropriate to use the D[3,2].

Figure 5: Illustration of the D[4,3] and D[3,2] on a particle size distribution where a significant proportion of fines are present

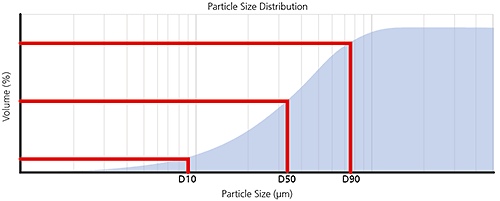

For volume-weighted particle size distributions, such as those measured by laser diffraction, it is often convenient to report parameters based upon the maximum particle size for a given percentage volume of the sample.

Percentiles are defined as XaB where:

X= parameter, usually D for diameter

a = distribution weighting, e.g. n for number, v for volume, i for intensity

B = percentage of sample below this particle size e.g. 50%, sometimes written as a decimal fraction i.e. 0.5

For example, the Dv50 would be the maximum particle diameter below which 50% of the sample volume exists - also known as the median particle size by volume.

The most common percentiles reported are the Dv10, Dv50 and Dv90, as illustrated in the frequency and cumulative plots below.

Figure 6: Illustration of volume percentiles in terms of cumulative and frequency plots

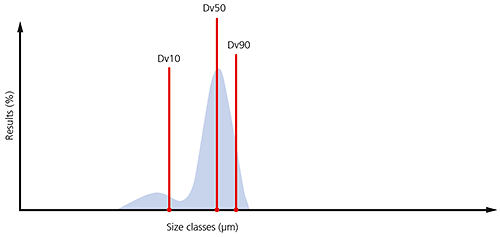

By monitoring these three parameters it is possible to see if there are significant changes in the main particle size, as well as changes at the extremes of the distribution, which could be due to the presence of fines, as shown in the particle size distribution below, or oversized particles/agglomerates.

Figure 7: Illustration of the Dv10, Dv50 and Dv90 on a typical particle size distribution where a significant proportion of fines are present

As well as particle size, the shape of constituent particles can also have a significant impact upon the performance or processing of particulate materials. Many industries are now also making particle shape measurements in addition to particle size measurements in order to gain a better understanding of their products and processes. Some areas in which particle shape can have an impact include:

Particle shape can also be used to determine the state of dispersion of particulate materials, specifically if agglomerates or primary particles are present.

Particles are complex 3-dimensional objects and, as with particle size measurement, some simplification of the description of the particle is required in order to make measurement and data analysis feasible. Particle shape is most commonly measured using imaging techniques, where the data collected is a 2-dimensional projection of the particle profile. Particle shape parameters can be calculated from this 2-dimensional projection using simple geometrical calculations.

Figure 8: Conversion of a particle image into a 2D binary projection for shape analysis

The overall form of a particle can be characterized using relatively simple parameters such as aspect ratio. If we take as an example the image of the particle below, the aspect ratio can simply be defined as:

Aspect ratio = width/length

Figure 9: Illustration of length and width on a needle shaped particle image

Aspect ratio can be used to distinguish between particles that have regular symmetry, such as spheres or cubes, and particles with different dimensions along each axis, such as needle shapes or ovoid particles. Other shape parameters that can be used to characterize particle form include elongation and roundness.

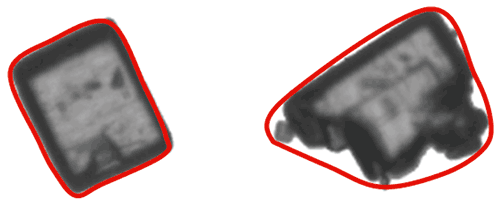

As well as enabling the detection of agglomerated particles, the outline of a particle can provide information about properties such as surface roughness. In order to calculate particle outline parameters, a concept known as the convex hull perimeter is used. In simple terms the convex hull perimeter is calculated from an imaginary elastic band which is stretched around the outline of the particle image, as shown in the image below.

Figure 10: Illustration of the convex hull for two different shapes of particle

Once the convex hull perimeter has been calculated we can then define parameters based upon it, such as convexity or solidity where:

• convexity = convex hull perimeter/actual perimeter

• solidity = area bound by actual perimeter/area bound by convex hull perimeter

Particles with very smooth outlines will have a convexity/solidity value close to 1, whereas particles with rough outlines, or agglomerated primary particles, will have consequently lower convexity/solidity values.

Some shape parameters capture changes in both particle form and outline. Monitoring these can be useful where both form and outline may influence the behaviour of the material being measured. The most commonly used parameter is circularity, where

• Circularity* = perimeter/perimeter of an equivalent area circle

*This is sometimes defined as: (perimeter/perimeter of an equivalent area circle)2

where it is also referred to as HS (high sensitivity) circularity to avoid confusion with the above definition.

Circularity is often used to measure how close a particle is to a perfect sphere, and can be applied in monitoring properties such as abrasive particle wear. However, care should be exercised in interpreting the data, since any deviations could be due to either changes in surface roughness or physical form, or both.

While circularity can be very useful for some applications, it is not suitable for all situations. To date, there is no definition of a universal shape parameter that will work in every case. In reality, careful consideration is necessary to determine the most suitable parameter for each specific application.

Zeta potential is a measure of the magnitude of the electrostatic or charge repulsion or attraction between particles in a liquid suspension. It is one of the fundamental parameters known to affect dispersion stability. Its measurement provides detailed insight into the causes of dispersion, aggregation or flocculation, and can be applied to improve the formulation of dispersions, emulsions and suspensions.

The speed with which new formulations can be introduced is the key to product success. Measuring zeta potential is one of the ways to shorten stability testing, by reducing the number of candidate formulations and hence minimizing the time and cost of testing as well as improving shelf life.

In water treatment, monitoring dosage using zeta potential measurements can reduce the cost of chemical additives by optimizing dosage control.

Zeta potential measurement has important applications in a wide range of industries including: ceramics, pharmaceuticals, medicine, mineral processing, electronics and water treatment.

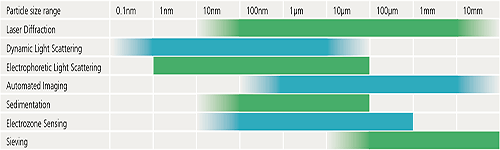

There is a wide range of commercially available particle characterization techniques that can be used to measure particulate samples. Each has its relative strengths and limitations and there is no universally applicable technique for all samples and all situations.

When deciding which particle characterization techniques you need, a number of criteria must be considered:

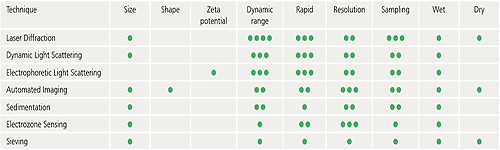

The following table is designed to provide some basic guidelines to help you decide which of some of the commonly used techniques could be most suitable for a particular application. The particle size ranges indicated are a guide only and exact specifications may vary from one instrument to another.

Virtually all particle characterization techniques will involve a degree of subsampling in order to make a measurement. Even particle counting applications where the entire contents of a syringe are measured, for example, will only examine a small fraction of all the syringes on a production line.

It is worth pointing out that the root cause of issues around unreliable measurements is very often related in some way to sampling. It is therefore essential that the subsample measured by the instrument is as representative as possible of the whole.

Where instruments (laser diffraction for example) require presentation of the sample as a stable dispersion, the effects of any sampling issues are minimized by homogenizing, stirring and recirculating the material. This does not, however, deal with the challenge of taking a representative 10g aliquot from a 10,000 kg batch for example.

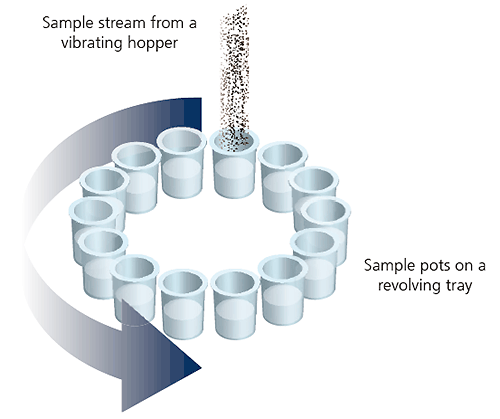

One common method that is widely used to increase the robustness of powder sampling is a device known as a spinning riffler.

Figure 11: Illustration of a spinning riffler device

In the spinning riffler, a number of subsamples are taken at regular intervals from powder flowing through a hopper into a rotating array of containers. This ensures that if any sample segregation takes place within the hoppers, each container should contain a representative subsample.

Many particle characterization techniques require the sample to be analyzed in a dispersed form where the individual particles are spatially separated. In order to do this there are two basic approaches:

In a wet dispersion, individual particles are suspended in a liquid dispersant. The wetting of the particle surfaces by the dispersant molecules lowers their surface energy, reducing the forces of attraction between touching particles. This allows them to be separated and go into suspension.

For dispersants with high surface tension, such as water, the addition of a small amount of surfactant can significantly improve the wetting behavior and subsequent particle dispersion.

In order to disperse individual particles it is usual to apply some energy to the sample. Often this is through stirring or agitation, but for very fine materials or strongly-bound agglomerates, ultrasonic irradiation is sometimes used.

In microscopy-based techniques, wet sample preparation methods can be used to disperse the sample onto a microscope slide. Subsequent evaporation of the dispersant then allows analysis of the dispersed particles in the dry state.

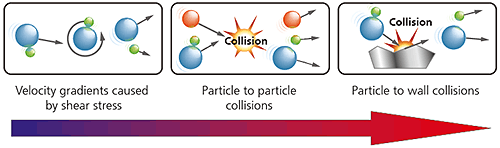

In a dry powder dispersion, the dispersant is usually a flowing gas stream, most typically clean dry air. The nature of the dry dispersion process means this is normally a higher energy process than wet dispersion. As shown below, three different types of dispersion mechanism act upon the sample. In order of increasing energy input they are:

Figure 12: Illustration of the three dry powder dispersion mechanisms with increasing energy/aggressivity

The dispersion mechanism that is most dominant will depend upon the design of the dispersant, with particle-wall impaction providing a more aggressive high energy dispersion than particle-particle collisions or shear stresses.

By eliminating the need to dispose of costly and potentially harmful solvents, dry dispersion is often an attractive option. However, dry dispersion is not suitable for very fine powders (<1 micron) because the high particle-particle forces of attraction in these materials are very difficult to overcome. Care should be taken with fragile particles to ensure that only sufficient energy is applied to the sample to obtain dispersion and that particles are not being broken during the dispersion process. In such cases a wet dispersion method should be used as a method validation reference.

Laser diffraction is a widely-used particle sizing technique for materials ranging from hundreds of nanometers up to several millimeters in size. The main reasons for its success are:

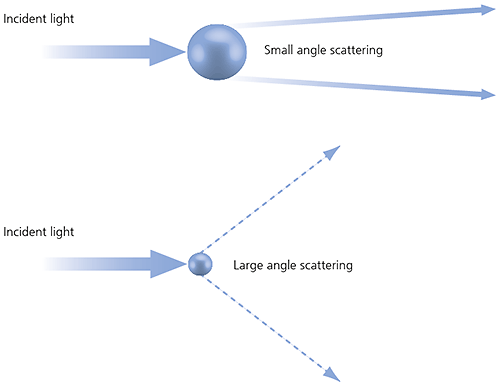

Laser diffraction measures particle size distributions by measuring the angular variation in the intensity of light scattered as a laser beam passes through a dispersed particulate sample. Large particles scatter light at small angles relative to the laser beam and small particles scatter light at large angles, as illustrated below. The angular scattering intensity data is then analyzed to calculate the size of the particles responsible for creating the scattering pattern, using the Mie theory of light scattering. The particle size is reported as a volume-equivalent sphere diameter.

Figure 13: Scattering of light from small and large particles

Laser diffraction uses Mie theory of light scattering to calculate the particle size distribution, assuming a volume-equivalent sphere model.

Mie theory requires knowledge of the optical properties (refractive index and imaginary component) of both the dispersant and the sample being measured.

Usually the optical properties of the dispersant are relatively easy to find from published data, and many modern instruments will have in-built databases that include common dispersants.

For samples where the optical properties are not known, the user can either measure them or make an educated guess and use an iterative approach based upon the fit of the modeled data versus the actual.

A simplified approach is to use the Fraunhofer approximation, which does not require the optical properties of the sample. However it should be used with caution when working with samples which might contain particles below 50 µm or particles which are relatively transparent.

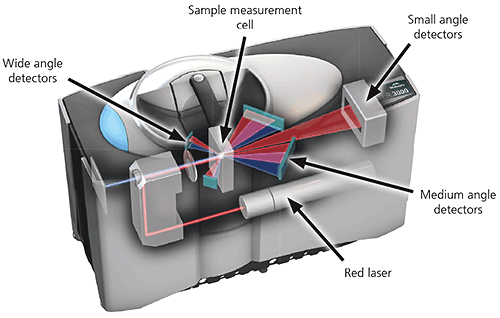

A typical laser diffraction system is made up of three main elements:

1. Optical bench. A dispersed sample passes though the measurement area of the optical bench, where a laser beam illuminates the particles. A series of detectors then accurately measures the intensity of light scattered by the particles within the sample over a wide range of angles.

Figure 14: Optical layout of a state-of the-art laser diffraction instrument

2. Sample dispersion units. Sample handling and dispersion are controlled by either a wet or a dry sample dispersion unit. These units ensure the particles are delivered to the measurement area of the optical bench at the correct concentration and in a suitable, stable state of dispersion.

Wet sample dispersion units use a liquid dispersant, aqueous or solvent-based, to disperse the sample. In order to keep the sample suspended and homogenized it is recirculated continuously through the measurement zone.

Dry powder sample dispersion units suspend the sample in a flowing gas stream, usually dry air. Normally the entire sample passes once only through the measuring zone, therefore it is desirable to capture data at rapid speeds, typically up to 10 kHz, in order to ensure representative sample measurement.

3. Instrument software. The instrument software controls the system during the measurement process and analyzes the scattering data to calculate a particle size distribution. In more advanced instrumentation it also provides both instant feedback during method development and also expert advice on the quality of the results.

The application of laser diffraction is covered by the international standard ISO 13320: 2009, which is recommended reading for anyone who uses this technique on a routine basis.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS), sometimes referred to as photon correlation spectroscopy (PCS) or quasi-elastic light scattering (QELS), is a non-invasive, well-established technique for measuring the size of particles and macromolecules typically in the submicron region down to below 1 nanometer. It can be used to measure samples which consist of particles suspended in a liquid, e.g. proteins, polymers, micelles, carbohydrates, nanoparticles, colloidal dispersions, and emulsions

Key advantages include:

Particles in suspension undergo Brownian motion caused by thermally-induced collisions between the suspended particles and solvent molecules.

If the particles are illuminated with a laser, the intensity of the scattered light fluctuates over very short timescales at a rate that is dependent upon the size of the particles; smaller particles are displaced further by the solvent molecules and move more rapidly. Analysis of these intensity fluctuations yields the velocity of the Brownian motion and hence the particle size using the Stokes-Einstein relationship.

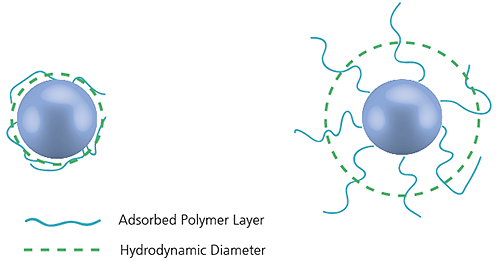

The diameter measured in dynamic light scattering is called the hydrodynamic diameter and refers to the way a particle diffuses within a fluid. The diameter obtained by this technique is that of a sphere that has the same translational diffusion coefficient as the particle being measured.

Figure 15: Illustration of the reported hydrodynamic diameter in DLS being larger than the 'core' diameter

The translational diffusion coefficient will depend not only on the size of the particle 'core', but also on any surface structure, as well as the concentration and type of ions in the medium. This means that the size will be larger than that measured by electron microscopy, for example, where the particle is removed from its native environment.

It is important to note that dynamic light scattering produces an intensity-weighted particle size distribution, which means that the presence of oversized particles can dominate the particle size result.

A conventional dynamic light scattering instrument consists of a laser light source, which is converged by a lens to a focus in the sample. Light is scattered by the particles at all angles and a single detector, traditionally placed at 90° to the laser beam, collects the scattered light intensity. The intensity fluctuations of the scattered light are converted into electrical pulses, which are fed into a digital correlator. This generates the autocorrelation function, from which the particle size is calculated.

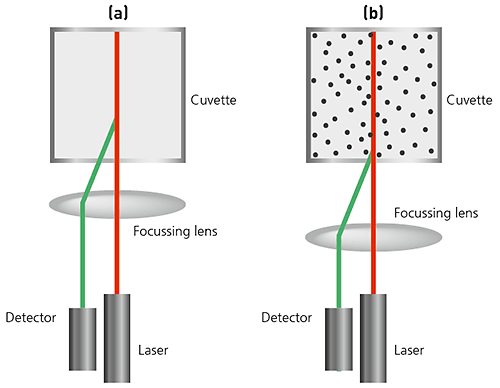

In state-of-the art instruments, NIBS (non-invasive backscatter) technology extends the range of sizes and concentrations of samples that can be measured.

The sizing capability in these instruments detects the light scattered at 173° as shown below. This is known as backscatter detection. In addition, the optics are not in contact with the sample and hence the detection optics are said to be non-invasive.

There are many advantages of using non-invasive backscatter detection:

Figure 16: Illustrations of NIBS-based optics in a DLS system (a) For small particles, or samples at low concentrations, it is beneficial to maximize the amount of scattering from the sample. As the laser passes through the wall of the cuvette, the difference in refractive index between the air and the material of the cuvette causes 'flare'. This flare may interfere with the signal from the scattering particles. Moving the measurement position away from the cuvette wall towards the centre of the cuvette will remove this effect. (b) Large particles or samples at high concentrations scatter much more light. Measuring closer to the cuvette wall reduces the effect of multiple scattering by minimizing the path length through which the scattered light has to pass.

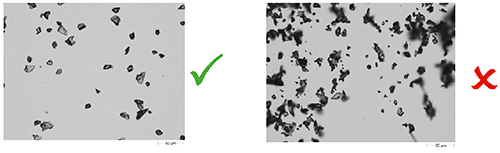

Automated imaging is a high resolution direct technique for characterizing particles from around 1 micron up to several millimeters in size. Individual particle images are captured from dispersed samples and analyzed to determine their particle size, particle shape and other physical properties. Statistically-representative distributions can be constructed by analyzing tens to hundreds of thousands of particles per measurement.

Static imaging systems require a stationary dispersed sample whereas in dynamic imaging systems the sample flows past the image capture optics. The technique is often used in conjunction with ensemble-based particle sizing methods such as laser diffraction, to gain a deeper understanding of the sample or to validate the ensemble-based measurements. Typical applications include:

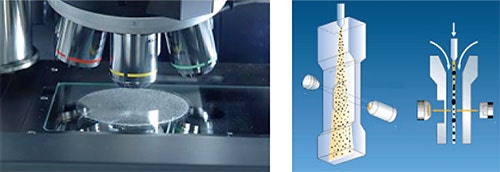

A typical automated imaging system is composed of three main elements:

1. Sample presentation and dispersion

This step is critical to getting good results: spatial separation of individual particles and agglomerates in the field of view is the goal. A range of sample presentation methods is available depending upon the type of sample and instrumentation employed. Dynamic imaging instrumentation uses a flow cell through which the sample passes during the measurement. Static imaging techniques use a flat surface such as a microscope slide, a glass plate or a filter membrane. Automated dispersion methods are desirable to avoid potential operator bias.

Figure 17: Illustration of the importance of sample dispersion for automated particle imaging

2. Image capture optics

Images of individual particles are captured using a digital CCD camera with appropriate magnification optics for the sample in question. In dynamic imaging systems the sample is typically illuminated from behind the sample, whereas static imaging systems offer more flexibility in terms of the sample illumination e.g. episcopic, diascopic, darkfield, etc. Polarizing optics can also be used for birefringent materials such as crystals. The most advanced dynamic imaging systems use a hydrodynamic sheath flow mechanism to achieve consistent focus for even very fine particles.

Figure 18: Illustration of static imaging (left) and dynamic imaging (right) optical arrangements

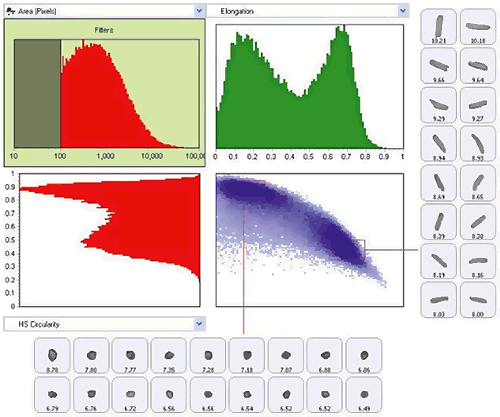

3. Data analysis software

Typical instruments measure and record a range of morphological properties for each particle. In the most advanced instruments, graph and data classification options in the software ensure that extracting the relevant data from your measurement is as straightforward as possible, via an intuitive visual interface. Individually-stored grayscale images for each particle provide qualitative verification of the quantitative results.

Figure 19: Use of scattergram tool to show classification of the sample by both size (elongation) and shape (HS Circularity)

Electrophoretic light scattering (ELS) is a technique used to measure the electrophoretic mobility of particles in dispersion, or molecules in solution. This mobility is often converted to zeta potential to enable comparison of materials under different experimental conditions.

The fundamental physical principle is that of electrophoresis. A dispersion is introduced into a cell containing two electrodes. An electrical field is applied to the electrodes and any charged particles or molecules will migrate towards the oppositely charged electrode. The velocity with which they migrate is known as the electrophoretic mobility and is related to their zeta potential.

This velocity is measured by the laser Doppler technique, of which there are two implementations: one to determine a frequency shift, which can give a full zeta potential distribution, and a second, phase analysis light scattering (PALS), where the phase shift is measured. PALS is a more sensitive method, but only gives an average zeta potential value.

State-of-the art instruments often combine DLS and ELS in one system, giving the capability to measure both particle size and zeta potential.

The physical properties of particulate-based materials also have an influence on the bulk or macro properties of products and materials.

For instance, the rheological (flow/deformation) behavior of a formulated product can be related directly to properties of its ingredients, such as particle size, particle shape and suspension stability. Therefore measuring the rheology of a formulation gives an indication of its colloidal state and interactions between its different constituents. Rheology-based measurements can help predict formulation behaviors such as;

Therefore when working with particulate-based formulations it is also important to consider macro properties, such as rheology, in order to better understand the behavior of formulated materials. The details of rheology theory and application are outside the scope of this publication, but many introductory materials are available on the Malvern Panalytical website.

Application note : Basic principles of particle size analysis

Webinar : An introduction to particle size

Webinar: Particle size Masterclass 1: The basics

Webinar: Particle size Masterclass 2: Which technique is best for me?

Webinar: Particle sizing Masterclass 3: Method development

Webinar: Particle size Masterclass 4: Setting specifications

Article: Particle shape - An important parameter

Webinar : Imaging Masterclass 1: Basic principles of particle characterization by automated image analysis

Technical note: Zeta potential : An introduction in 30 minutes

Pierre Gy: 'Sampling of Particulate Material, Theory and Practice' 2nd Edition Elsevier, Amsterdam (1982)

Whitepaper: Sampling for particle size analysis

Webinar : Estimation of fundamental sampling error in particle size analysis

Webinar: Laser diffraction Masterclass 1: Laser diffraction explained

Webinar: Laser diffraction Masterclass 2: Wet method development

Webinar: Laser diffraction Masterclass 3: Dry method development

Webinar: Laser diffraction Masterclass 4: Optical properties

Webinar: Laser diffraction Masterclass 5: Setting particle size specifications

Webinar: Laser diffraction Masterclass 6: Troubleshooting

Webinar: Laser diffraction Masterclass 7: Comparison of light scattering and image analysis techniques

ISO 13320:2009 Particle size analysis -- Laser diffraction methods

Whitepaper: The enduring appeal of laser diffraction particle size analysis

Technical note: Dynamic light scattering : An Introduction in 30 Minutes

Whitepaper: Dynamic light scattering: common terms defined

Technical note: Zeta potential : An introduction in 30 minutes

Webinar : Imaging Masterclass 1: Basic principles of particle characterization by automated image analysis

Webinar: Imaging Masterclass 2: Sample preparation techniques for particle size and shape measurements

Webinar: Imaging Masterclass 3: Static vs. dynamic image analysis

ISO 13322-1:2014 Particle size analysis -- Image analysis methods -- Part 1: Static image analysis methods

ISO 13322-2:2006 Particle size analysis -- Image analysis methods -- Part 2: Dynamic image analysis methods